|

| Presenting Historical Ken as Paul Revere |

So here we are, scarcely a month later, and we got slammed with mid-90 degree temperatures and high humidity, making for a miserable day for any sane person.

I did say "sane"?

Haha---we're talking about "Historical Ken" here, you know...the middle-aged guy who loves to wear clothing from days of old and pretend to live in the past - - - yes, even on this sultry Louisiana summer-type day, I was there dressed as if I were living in the 1770s.

"Sane" indeed!.

The price we pay to present history, eh?

|

| Shining up the pewter... |

And I get laughed at for it sometimes, whether on Facebook when I post something patriotic, or at times right to my face during a discussion. And, like I said, it's usually the younger (under 35) set that thinks of me as some old relic who just doesn't know any better.

I would like to say I don't care, but I do. I want to see patriotism make a come back.

And it just may - - -

Have you noticed lately that the Revolutionary War era - the times of our Founding Fathers - has been pretty popular as of late?

In the past decade or so there have been a number of successful television shows centered around America's founding years: HBO's "John Adams," The History Channel's "Sons of Liberty" (really a bad movie, but it did well in the ratings, showing that people are interested), AMC's "TURN: Washington's Spies" series, and the very popular play/musical "Hamilton."

All showing respectable ratings (or, for "Hamilton," high acclaim from reviewers and sell out shows).

That's got to tell you something.

Interest in our Nation's founding is growing.

I am so excited!!

|

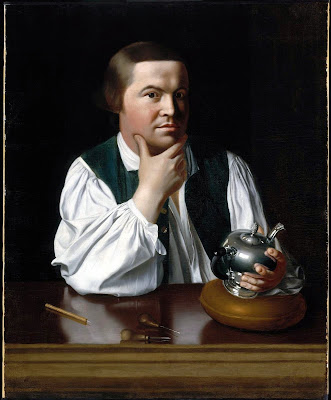

| The real Paul Revere, as painted by John Singleton Copley ca1770 Hmmm...looks like I'll have to get myself a green waistcoat, eh? |

I was a little nervous initially. I really had to be 'on,' you know? I knew I had to get it right. For the most part, I did, though I had a little mix up for the first presentation, but I recovered for the rest of them. Yes, I know that I don't look like Mr. Revere, but it helps that most people don't know what he actually looked like any way (even though there is that very famous painting of him by John Singleton Copley from roughly 1770).

Still, I have been enjoying it immensely.

As I have been doing with other reenactments postings, I will let the photos taken do most of the talking here, though I have added my own commentary as well.

Again, many of the following pictures were taken with my camera, but quite a few were taken by B&K Photography (good friends of mine who are magnificent photographers) and are noted as such with watermarks on each of their pictures.

Enjoy - - -

But I also want to put an end to the modern idea that Paul Revere was virtually unknown until Longfellow's 1860 poem. Nothing could be further from the truth. He was a well-respected and well-known man & silversmith in Boston, and was also known for his engravings (among numerous other activities) - this is besides his ride on the night before the Battle of Lexington & Concord, of which made news in dozens of broadsides/newspapers. In fact, Revere's ride is mentioned in a history book originally published in 1850: "The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution, Volume 1" by Benson J. Lossing.

I suppose I can also say this was the first official outing for my new reenacting group, Citizens of the American Colonies. One of our members came out for her very first time:

|

| Ross is another long-time RevWar-era reenactor. Though not shown in this picture, he is a weaver, a spinner, and a maker of woven belts. A man of numerous talents! |

|

| Here are a couple of riflemen from the Philadelphia Rifle Company. Rich, the fellow in green, is also a Civil War reenactor. |

|

| Here you see Rich and I together - both belonging to different aspects of the same team. |

The Queen’s Rangers, a British provincial unit that fought on the Loyalist side during the American Revolutionary War, started off under the command of Robert Rogers who was the founder and commander of the first Ranger Regiment (Rogers Rangers) during the French and Indian War (1756–1763).

When

the American Revolutionary War broke out in earnest in 1775, about fifty Loyalist

regiments were raised, including the one that Robert Rogers raised in New York.

It first assembled in August 1776 and grew to 937 officers and men, organized

into eleven companies of about thirty men each, and an additional five troops

of cavalry.

|

| This reenacting unit was founded in 2014 by Scott Mann, who had been in the hobby for many years. He formed the unit for the same reason all had joined - for the love of history. |

|

| A Queen's Ranger Loyalist and a Boston Patriot. |

|

| Call me crazy, but this member of the Queen's Rangers certainly reminds me of someone on TV...hmmm... (hint: anyone a fan of AMC's "Turn - Washington's Spies" ?) |

What would a Revolutionary War reenactment be without a battle?

|

| What you see here is the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment marching out of the fort. |

Although the terms militia and minutemen are sometimes used interchangeably today, in the 18th century there was a decided difference between the two. Militia were men in arms formed to protect their towns from foreign invasion and ravages of war. Minutemen were a small hand-picked elite force which were required to be highly mobile and able to assemble quickly. Minutemen were selected from militia muster rolls by their commanding officers. Typically 25 years of age or younger, they were chosen for their enthusiasm, reliability, and physical strength. Usually about one quarter of the militia served as Minutemen, performing additional duties as such. The Minutemen were the first armed militia to arrive or await a battle.

An officer from the 43rd Regiment of Foot was sent to the North Bridge in Concord with a number of light infantry. Minutemen from Concord, Acton, Littleton, and other towns combined forces. After a few volleys were fired, the British light infantry retreated back to the Concord Common area. Lacking central command, with each company of Minutemen loyal to their own town, they did not pursue the redcoats. In the running battle that ensued fifteen miles back to Boston the Massachusetts militia would see their last action as Minutemen in history. The militia would go on to form an army, surrounding Boston and inflicting heavy casualties on the British army at Bunker and Breed's Hill.

|

| Although lacking central command, the Minutemen were still better organized and battle-tested than any other part-time military. |

|

| Though this was a smaller event, the soldiers certainly gave quite a show to the visitors. |

|

| A Queen's Ranger gets it by the butt end of a musket. |

|

| Unfortunately, due to previous situations in the City of Detroit during the 1970s and 80s, many of the historic structures that make up the Historic Fort Wayne complex have been destroyed beyond repair, as you can see by this and a few of the other photos. Thank God for the volunteers that have been able to save what they have, including the fort and barracks and a few of the houses (including the one a few of us use during the Holiday season for Christmas at the Fort). That being said, there is one tiny piece of a bright side in a sort of selfish manner for these dilapidated houses: they do make a great backdrop for a battle, looking every bit the bombed out houses they are. |

|

| Here we see "Molly Pitcher." There is some debate among historians as to who the "real" Molly Pitcher is. Most believe that the title is a composite character of all of the women who fought in the Continental Army. |

The

actions of Molly Pitcher are usually attributed to one Mary Ludwig Hays

McCauley. The nickname "Molly" was common for women named

"Mary".

She

married William Hays, a barber, in 1769. Hays was a Patriot involved in the

1774 boycott of British goods that arose as protest for the unfair tax being

placed on the colonies.

In

1777, Hays enlisted in the Continental Army and was trained as an artilleryman.

Mary followed and joined a group of camp followers.

They

took care of the troops, washed clothes, made food, and helped care for the

sick or injured soldiers.

|

| During the Battle of Monmouth, in June of 1778, Mary Hays carried water from a spring to the thirsty soldiers under heavy fire from the British. When her husband collapsed (sources claim either heat stroke or injury) and was carried off of the battlefield, Mary Hays took his place at his cannon. Once, a cannon ball came so close, that it actually went between her legs, ripping her petticoat. She is only known to have said something along the lines of, "Well, that could have been worse," and went back to firing her cannon. |

By the late 18th century, artillerymen were considered elite troops. In an age of widespread illiteracy, soldiers who could do the geometric calculations necessary to place a cannonball on target must have seemed almost as wizards.

|

| Among the cannon most used in the Revolution by all armies was the standard smooth-bore muzzle-loading gun which had been little changed in the previous two hundred years and which would serve as the principal artillery weapon of most of the world’s armies for another hundred. |

|

| They were cast of iron or bronze; loaded with a prepared cartridge of paper or cloth containing gunpowder, followed by a projectile. |

|

| It was fired by igniting a goose-quill tube containing gunpowder, or "quickmatch," inserted into a vent-hole that communicated with the charge in the gun... |

|

| ...and when fired, the recoil threw it backward, necessitating it being wrestled back into the firing position by the gun crew. |

In medicine, the

views held by 18th century physicians are very different from those held by

medical practitioners of today. Physicians in the 18th century had no knowledge

of bacteria, germs, or viruses, nor of the fact that disease was spread by

them. Therefore, they did not practice sterilization, or personal or hospital

hygiene.

There

were approximately 3,500 practicing physicians in the colonies in 1775. Some

were trained at the first medical college to be opened in America, the

Pennsylvania Hospital, which opened in Philadelphia in 1768. It was followed by

Kings College which opened two years later in New York. Because these colleges

accepted only a handful of doctors for training, most American doctors were

trained through apprenticeships, receiving seven years of training before they

were officially considered physicians.

|

| While these doctors were highly trained by the standards of their time, their services were not available to all of the general population. Many people lived too far away from any doctors to use their services, and other people did not have access to doctors because of social customs or beliefs. For these reasons, people other than doctors often assumed the role of caring for the sick or injured. |

Despite

this varied training, Revolutionary War surgeons did a notable job of

attempting to save lives. Most were competent, honest, and well-intentioned,

but conditions and shortages in medical supplies placed an overwhelming burden

on them. Besides caring for those wounded in battle, the camp surgeon was

responsible for caring for the camp's diseased soldiers. The camp surgeon was

constant alert for unsanitary conditions in camp that might lead to disease. He

spent a good deal of time aiding patients rid their bodies of one or more of

the four humors. Common diseases suffered by soldiers were dysentery, fever,

and smallpox.

|

| Surgeon's "tools." |

|

| Most wounds were caused by musket balls or the bayonet. Bullets were removed only if within easy reach of the surgeon. If a wound had to be closed, a piece of onion was placed in the cavity before closure, and the wound reopened in 1 to 2 days. |

|

| Colonial physicians saw the development of pus a few days after

injury as a sign of proper wound digestion.

Surgeons

treated wounds by incising the wounds and fishing around with their fingers for

the musket

ball or fragment.

|

|

| A successful operation! |

|

| A few friends popped in to visit me while at Fort Wayne. Regular readers may or may not recognize these folks as Civil War reenactors, but all do or plan to do colonial as well in some form in the near future. In fact, Larissa on the left is a master presenter at the 1760 Daggett House in Greenfield Village. |

|

| My wife and I during a quiet moment in the afternoon. Between Civil War and colonial, Patty is a bit overwhelmed with all of this time-traveling, but she does enjoy her time in the past, especially when she can spin on her wheel. Oh, and spend time with her husband. |

A number of firsts were accomplished this weekend:

first time setting up my own tent at a colonial reenactment

first time presenting as Paul Revere at a colonial reenactment

first time bringing out my own accessories at a colonial reenactment

and the first time presenting with Ben Franklin

I enjoyed it very much and am really looking forward to doing more, especially now that I will be bringing my own articles. And it's my great hope and wish that my friends will play a larger role in this adventure. I believe we are at the beginning of a growing era in the living history world - one which can help to return the excitement and pride of our Nation's past.

Yes...bigger and better things in the colonial world are on the horizon.

I can feel it...

Information for this posting came from numerous sources, including

Military Medicine During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

US History.org

"The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution, Volume 1" by Benson J. Lossing

Also, David Marquis, Caleb Church, and Dalton Lee helped out greatly with information as well.

Please visit B&K's Photography Facebook page: HERE

To read more of my postings on the colonial life and RevWar reenacting, please check out the following links:

A History of the Queen's Rangers

In the Good Old Colony Days

Kensington 2015

Paul Revere: Listen My Children and You Shall Hear...

Travel and Taverns

With Liberty and Justice For All: The Fight for Independence at the Henry Ford Museum

Colonial Ken Visits Greenfield Village for New Year's 2015/16

Colonial Ken & Friends - 4th of July 2014: Celebrating Independence Day in a Colonial Way

Colonial Christmas

Life on the 18th Century Frontier

Cooking on the Hearth - The Colonial Kitchen

A Midwife's Tale - Film Immersion

|

| Well, Ken... Yes, Ken? Until next time, see you in time. (photo by Larissa Fleishman) |

.